Experiential Avoidance

The tendency to avoid pain does not make you abnormal. In fact it places you squarely in the human race. Over the last decade of doing therapy, here are a few avoidance behaviors I’ve encountered:

I avoid letting people see the real me because I might be judged

I avoid thinking about the event because it’s painful

I avoid crying because I feel like I’m losing control

I avoid friendships because people usually let me down

I avoid conflict because my partner could abandon me

I avoid showing my true self because others may reject me

I avoid hope because I hate feeling disappointed

Our most basic wiring is hedonic which derives from the word “hedonism.” This means we are wired to move towards pleasure and away from pain. Avoidance is normal and even adaptive in some contexts. For example, learning to avoid a hot stove because it will burn your hand fosters survival. For our primitive ancestors, if the shadowy figure on the hillside gave them bear rather than blueberry bush vibes, they were better off avoiding it. However, when you find yourself putting off your taxes, or avoiding intimacy, it may not be as adaptive. Hence, avoidance may function okay in a survival landscape, but avoidance is antithetical to living a full and meaningful life in our modern-day world.

In addition to external experiences, we are also inclined to avoid negative internal experiences such as unwanted thoughts, feelings, sensations, and memories. An idea that comes from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is that suffering comes not from the experience of emotional pain, but from our attempted avoidance of that pain. Where, in fact, the struggle to eliminate pain becomes a source of pain itself.

The formula [PAIN X RESISTANCE = SUFFERING] captures this phenomenon. ACT coined the term experiential avoidance to refer to not wanting to have a particular emotion, sensation, or feeling. When we engage in experiential avoidance, we view these internal phenomena as problems that need to be eliminated and go to war with them. It may surprise you to learn that eating or using substances for enhancement is another pathway of avoidance. The desire to feel better is a message that how we’re feeling right now isn’t enough (Lillis, Dahl, & Weineland, 2014). This is referred to as the control agenda.

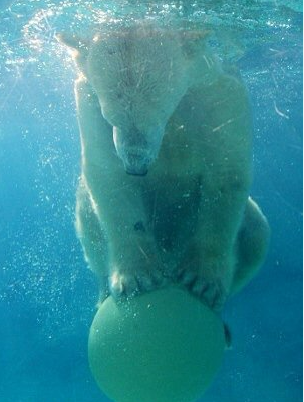

Have you ever tried holding a beach ball underwater? How long were you able to keep that up? Probably not long.

The effort to keep uncomfortable emotions and images at bay is exhausting and undermines our ability to put our efforts towards fulfilling activities.

Furthermore, “our unwillingness to stay in contact with internal experiences is thought to underlie many unhealthy ‘escape’ behaviors, such as substance use, risky sexual behavior, and deliberate self-harm, and may increase the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in people who have experienced a severe trauma” (Tull, 2022).

Practice:

Take a moment to consider where you have seen others avoid their emotions and discomfort.

Where have you seen yourself avoid? Or what have you done to not feel certain emotions or discomfort?

Consider important, vitalizing activities you started avoiding or gave up all together or didn’t try.

Consider whether avoidance works in the long run. Did these emotions become smaller or larger? Have you ever successfully eliminated an unwanted thought, feeling, image? Maybe you’ve experienced temporary relief from the distraction. What did it cost you to try?

You have probably heard the popular refrain, “what you resist, persists.”

I was surprised when I looked up the origins of this quote to find that what the pioneering Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung actually said was “what you resist not only persists, but grows in size.” In ACT we have a similar saying, “If you’re not willing to have it, you’re stuck with it.” Unfortunately, avoidance just doesn’t seem to work. It turns out that strategies like avoiding, suppressing, denying, or ignoring tend to perpetuate the very thing they seek to eliminate. Hayes and colleagues found that the more people avoid, the more depression, anxiety, trouble at work, and physical pain symptoms they report in addition to a generally poorer quality of life (Hayes et al. 2004).

Another problem is “once your start avoiding a few things, it gets more and more tempting to avoid a lot of things” (Hunt, 2016).

Regrettably, when we avoid, we don’t give ourselves the chance to learn anything new like that the thing we’ve been avoiding really isn’t that dangerous or that we are capable of coping. A well-lived life means doing things that involve discomfort (e.g., setting boundaries with a friend, resolving a conflict with family member, putting our art into the world). As Brene Brown puts it, “vulnerability is the bedrock of connection” and vulnerability can feel VERY uncomfortable.

So while avoiding difficult experiences feels automatic, like a natural instinct, we can untrain our avoidant tendencies and teach ourselves another way. Paradoxically, when we allow ourselves to sit with our unwanted feelings and confront our unwanted thoughts, we find that they pass. We are no longer giving energy to them and find that they will dissipate on their own.

This is hard to do right? Because sitting with pain is well…painful. But have you ever experienced an emotion that lasted forever? In my experience, no one has ever answered this question with a “yes.” Most emotions come in waves arising, peaking, and falling away if we allow them to pass through. Stopping them in their tracks keeps them stuck, unprocessed, and undigested. When we turn towards our feelings, we learn we are okay and that we can tolerate what is happening inside us even though it is uncomfortable.

This reminds us that not all pain is dangerous.

Similarly when we face an external stimulus (e.g., asking for help, confronting our partner about a resentment we hold, asking for a raise), we are likely to realize that it wasn’t as scary as it seemed and afterward we may even feel some relief.

This points us towards what we can do instead of avoid. For our internal experiences, “the solution is simple: You can be willing to feel stuff” (Lillis, Dahl, Weineland, 2014). Simple, however does not mean easy. As for external experiences, the opposite of avoidance is approach. In both cases, the more comfortable we become with being uncomfortable, the freer we are. Know that we don’t have to like the experience. We can not like and still do the thing. In fact, you probably already act with willingness and approach unpleasant things every day. For example, anytime we show up for work, attend a social activity, or go to the gym when we feel tired we are practicing willingness. Parents likely do this on a daily basis.

When you work with an ACT therapist, they will help you grow your willingness in the service of what matters to you. They will help you approach feared stimuli in a gradual manner. Your brain will learn that the feared outcome (e.g., “It will be awful,” “I won’t be able to handle it”) either does not happen or that you are able to cope. Over time you will build a sense of efficacy, or a belief in yourself, that you can do hard things whether that is feel your grief, go to social events which elicit anxiety, cope with uncertainty, or get through a panic attack. With more efficacy around coping with our experiences, we are then able to put the energy that was spent avoiding into meaningful life activities. An ACT therapist will help you get clear about your values (what matters to you in life) and align your actions with those values.

“Avoiding emotional struggle and practical difficulties is impossible when one has become committed to personally worthwhile long-term goals.”

In summary, learning to avoid a stimulus that is objectively dangerous is adaptive. But we tend to overestimate the things in life that are dangerous versus uncomfortable. When we can learn to face things in life that are uncomfortable but matter to us, like confronting our spouse, making a budget, showing our authentic self, we are better off. Paradoxically this brings us closer to thriving.

Click here to learn how to approach a valued activity you’ve been avoiding by designing your own behavioral experiment.

If you suffer from PTSD, you should approach your unwanted images and process your feelings with the support of a trusted therapist as this work can feel especially overwhelming.

References

Hunt, Melissa, G. (2016). Reclaim Your Life From IBS: A Scientifically Proven Plan for Relief without Restrictive Diets. Sterling, NY.

Lillis, Dahl, & Weineland. (2014). The Diet Trap: Feed Your Psychological Needs & End the Weight Loss Struggle Using Acceptance & Commitment Therapy. New Harbinger, CA.

Panayiotou, Karekla, & Mete. (2014). Dispositional Coping in Individuals with Anxiety Disorder Symptomatology: Avoidance Predicts Distress. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 3, 314-321.

Tull, Matthew. (2022). What is Experiential Avoidance. https://www.verywellmind.com/experiential-avoidance-2797358